Excerpt from image of Capt. George Lowther and his Company at Port Mayo in the Gulf of Matique, 1734, showing pirates in a makeshift tent.

Table of Contents:

- Introduction

- The Geography of New Providence

- The Pirates: Their Origins and Numbers

- Shelter, Trade, Food, and Rum: Living in Nassau

- Conclusion

- Endnotes

Introduction

By 1716, New Providence stood as a stronghold for pirates. Since past Bahamian residents and governments allowed pirates to enter and use their harbor for generations, this news surprised few among people familiar with New World maritime activity. John Graves, a former customs collector in Nassau, published a prediction in 1707 that the Bahamas would become a, “Shelter for Pyrates, if left without good Government and some Strength.” He further predicted, “that one small Pyrat with Fifty Men that are acquainted with the Inhabitants (which too many of them are) shall and will Ruin that Place, and be assisted by the loose Inhabitants; who hitherto have never been Prosecuted to effect, for Aiding, Abetting, and Assisting the said Villains with Provision.”1 Six years later, Grave’s predictions came true.

In the past decade, a premium channel television program, a billion-dollar video game franchise, and popular press publications all helped revive public awareness and interest in the Bahamas and its pirate past. These shows, games, and books are consistent in the manner they present the history of New Providence. In telling the stories of the pirates, the narratives usually centered on captains, their crews, and the British officials that confronted them. The recent portrayals of Nassau tend to follow what Hollywood and artistic mediums has done for generations. The romanticized image of the typical pirate base set at a remote Caribbean settlement features a group of wooden post-and-beam frame buildings, built near an elegant beach, and populated with pirates gallivanting with attractive women day and night. This common media depiction, while appealing to general audiences, is two-dimensional. This weak caricature does not delve deep into understanding what New Providence was like in 1716-1717, when Nassau’s pirate population was at its peak.

The Geography of New Providence

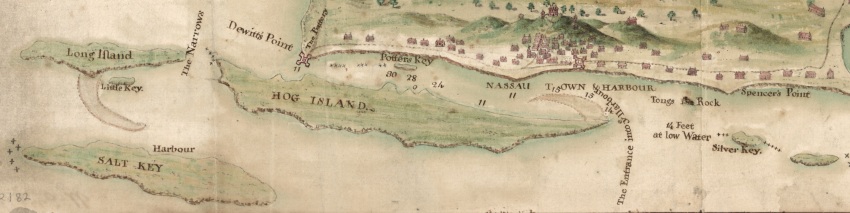

Excerpt from a Map of New Providence, mid eighteenth century. This excerpt concentrates on the harbor of Nassau. Note there are harbor depths featured here. While the depth of harbors changed over time, these later measurements give at least some idea of the harbor’s appearance earlier in the century.

To understand Nassau and the Bahamas in the 1710s requires an understanding of its geography. According to a writer on the history and conditions of the British colonies in 1708, New Providence measured twenty-eight miles at its longest points and eleven miles at its widest.2 Though the Bahamas has thousands of islands, New Providence stood as the center of power and population for the entire archipelago. This situation dates back well into the seventeenth century. Not long after the English began to settle the island, the core of the Bahama’s population center moved from the larger island of Eleuthera to New Providence. Sailors soon recognized the island as the center of the Bahamas. The maritime pilotage book, The English Pilot, the Fourth Book, first published in 1698 with several new editions in the early eighteenth century, described New Providence as, “the chief of all the Bahama Islands.”3

Nassau’s harbor on New Providence presented the best harbor for trade vessels in the Bahamas. Other islands did feature their own harbors, though none of them could accommodate large-sized vessels. Royal Island could harbor vessels of one hundred tons, but offered no sizeable water source. Hockin Islands allowed vessels of seventy tons or less. The most viable harbor after Nassau was Harbour Island. This small island’s bay dropped to eighteen or nineteen feet at low tide and featured an easily defended narrow entrance, but could only receive vessels of two hundred tons or smaller. Meanwhile, New Providence offered a large harbor that accommodated vessels of three to five hundred tons, provided fresh water via its shade-covered ponds and rock reservoirs that captured rainwater, and sat on the edge of a deep, navigable underwater canyon.4 Nassau offered a convenient harbor for vessels blown off the coast of Florida or the northern British colonies. John Graves said, “Upward [of] Fourteen Sail in a Year come into Providence Harbour for Shelter.” When these vessels took shelter in Nassau, some local Bahamians kept stocks of supplies they could sell to stranded mariners.5

The harbor of Nassau resided between the northeastern corner of New Providence and a smaller islet called Hogg Island.† This small, narrower tree-covered island, ran about four or five miles in length parallel to New Providence’s shore. The town of Nassau sat across the harbor from Hogg Island, just east of the town’s fort, and to the north of a large steep hill. Between Hogg Island and New Providence sat Nassau’s deep harbor with a depth of at least four fathoms (twenty-four feet). Within this harbor, hundreds of vessels could anchor, five hundred of them by one estimate. Oldmixon bitingly said the harbor could hold the entirety of the English Royal Navy.6 While a force of ships equal in number to the navy might anchor at Nassau, only the smaller navy vessels could have enter into this harbor because of a shallow area at the eastern end of the harbor and a sand bar at the western entrance prevented any ship larger than one of the Navy’s fourth-rate ships of the line from anchoring at Nassau. A sand bar with a depth of eight feet projected from the western end of Hogg Island, called West Point. At the end of the sand bar, directly in front of Nassau’s fort, stood a small channel of about two cables lengths (1,200 feet) in width. The channel offered an avenue around the bar. The waters near the fort also offered a sandy anchorage of eighteen feet at low tide and twenty feet during the spring tide. Even with the help of this deeper channel, a vessel with a large draft could not pass the bar nor the channel into the harbor between New Providence and Hogg Island.7

Nassau’s harbor, besides possessing the deepest anchorage in the Bahamas, also commanded a strategic position between Britain’s colonies on the eastern coast of America and the rest of the Caribbean to the south. John Graves described the Bahamas as being, “the very Center between Carolina and Jamaica.”8 It took little time to sail from New Providence to several significant ports. It took three days to travel between Nassau and the city of Havana and only twenty-four hours to reach the coast of Cuba. The trip from New Providence to Charleston took seven days and ten days to sail back from Charleston.9 Vessels went to Nassau frequently enough that the English Pilot included several sets of instructions for sailing to New Providence.10 Most importantly, the Bahamas sat astride the Old Bahama Channel that flowed across the northeastern coast of Cuba, the Windward Passage between Cuba and Hispaniola, and the New Bahama Channel on Florida’s eastern coast.‡ Each of these three channels featured heavy ship traffic. A vessel could strike at merchant ships traveling in these maritime corridors and retreat to the nearby protection of Nassau’s harbor or, if using a shallow-drafted vessel, hide at one of the many other islands in the Bahamas. With New Providence providing a significant shelter to trading vessels and raiders, control of Nassau was crucial, and made its control by pirates in the 1710s distressing to many colonial governments.

The Pirates: Their Origins and Numbers

The use of the Bahamas as an undisputed base for pirate operations began several months after the War of Spanish Succession ended. The earliest pirate raid from New Providence after the war, with a known date, came in August of 1713 when John Cockram led twenty men in a canoe or a periauger to the coast of Florida. For some of Cockram’s men, sailing to Florida was a familiar activity. Bahamians held a reputation for wrecking on the Florida coast, meaning they went and found wrecked ships from which they salvaged valuable goods or anything of use. Cockram and his small crew managed to take plunder worth £2,000 in their short cruise.11 Other small boat crews with a mix of locals and new arrivals from other colonies soon followed. They all used New Providence and as a base at some point. Among the pirates who started in these boats was Benjamin Hornigold, who began using a sloop, the Happy Return, in 1714.12 These small groups of pirates had no British government to stop their raids. The Lord Proprietors had not appointed a new governor to the Bahamas since 1704. The last remnant of the prior government, Thomas Walker, petitioned for help in suppressing the pirates. On one occasion, Walker gathered a crew and captured the pirate Daniel Stillwell and his vessel after his small crew took a Spanish launch on the coast of Cuba carrying 11,050 pesos. Benjamin Hornigold reacted to Walker’s actions by freeing Stillwell, threatened to burn Walker’s house, and declaring, “That all pirates were under his [Hornigold’s] protection.”13 Little could Walker or Hornigold have guessed a Spanish Treasure Fleet would soon alter Nassau and establish a population that would dwarf Hornigold’s crew and the other pirates who operated from the Bahamas before 1716.

On July 30, 1715, a hurricane on the coast of Florida caused an event that would spur a population boom in New Providence. Only a few days before the storm, a fleet of twelve ships containing riches belonging to Spain’s New World colonies sailed from the harbor at Havana. The fleet carried a registered treasure worth 6,388,020 pesos (or £1,437,304.10), 955 castellanos of gold dust and bars of an unspecified value, and other riches unknown in quantity since passengers and crew brought additional unregistered treasure in their personal luggage.14 On the night of July 30, the fleet happened to be sailing up the New Bahama Channel off of Florida. The hurricane wrecked eleven of the twelve vessels in the fleet, killed over 1,000 men, and stranded 1,500 more on the coast. The Spanish moved quickly to recover the fleet’s riches, salvaging 5,200,000 pesos worth of private and government treasure by the end of 1715 and 41,166 pesos worth of treasure from January to July of 1716 when they concluded their main salvaging efforts.15

While the Spanish tried to recover their treasure, many mariners from British colonies also attempted to “fish the wrecks,” a term used in several period documents for the taking or salvaging of treasure from the Spanish shipwrecks. In November, several groups of British mariners began organizing and sailing to go wrecking in Florida. By December, the colonial newspaper, the Boston News-Letter, began publishing reports on British vessels visiting the wrecks. Dozens of vessels fitted out for the wrecks over the following months. Seven or eight vessel made it to the wreck from Bermuda in late November or early December, along with a few Jamaican sloops. More vessels soon followed from Jamaica, Bermuda, Barbados, St. Thomas, and other ports. Some Spanish and French crews also joined the wreckers. By early 1716, Jamaica fitted out as many as twenty-two vessels for the wrecks. In the late winter or early spring of 1716, about a dozen Jamaican vessels tried to force Bermudan vessels off the wrecks. To find the shipwreck sites, some of the wreckers captured Spaniards who knew the locations of the wrecks. These same crews claimed they had licenses or patents from their governors to fish the wrecks, including ones issued by the governor of the Bahamas, even though the Bahamas had no official government.16

Of all the events surrounding the salvaging of Spanish treasure, the most notable came from a raid in December of 1715. On November 24, the sloops Eagle and Bersheba under Captains John Welles and Henry Jennings received their commissions from Jamaica Governor Archibald Hamilton for privateering.17 After capturing a Spanish launch, whose crew knew the location of the salvage camps, Spanish accounts said the British vessels landed 150 well-armed men between the two Spanish salvage camps. The raiders divided into three squads, each with a drum and flag. When the British force confronted the main salvage camp, the Spanish tried to bribe the raiders into leaving. Jennings’ and Welles’ men refused and left the Spanish no choice but to surrender. The British raiders took up to 120,000 pesos from the camp, along with some silver plate, three bronze swivel guns, and fifty copper ingots the size of bread loaves. The wreck robbers, carrying a fortune worth £27,000 in coinage alone, then sailed to the port of Nassau.18

After Captain Henry Jennings contingent of wreckers arrived in Nassau in January of 1716, the number of pirates operating from New Providence increased significantly, though determining their rate of growth and exact numbers is difficult. Pirate crews frequently came or left Nassau, fluctuated in size, swapped ships, and split off new crews from older ones. Some men stayed ashore and did not immediately rejoin another crew. All these factors create obstacles to estimating the growth of the pirate population in the Bahamas. Around March of 1716, three sloops, one French, one British, and one Spanish, spent eighteen days rallying four hundred pirates on New Providence together and then sailed to attack the Florida salvage camps. While Spanish forces prevented the pirates from taking the silver they had already collected from the wrecks, the pirates spent four days salvaging boxes containing a total of 12,000 pesos, “a lot of fabricated silver and a box marked with the Arms of the King Our Senor.”19 While stranded in the Bahamas in March of 1717, a Captain Matthew Musson reported seeing five crews using Nassau as their base with a combined strength of three hundred and sixty men. Two reports from May and October of 1717 placed the strength of the New Providence pirates between seven and eight hundred men, while another from July of 1717 stated that at least a thousand men sailed in vessels that used the Bahamas as their rendezvous.20 After news came from Bermuda of King George I’s pardon, the HMS Phoenix arrived in Nassau on February 23, 1718 and reported he saw, “about 500 [pirates], all Subjects of Great Britain & young Resolute Wicked fellows.”21 From 1716 to February of 1718, period accounts suggested New Providence harbored between 500 and 1,000 pirates at any one time.

The pirate population in Nassau originated from several different places, though some were not strangers to the Bahamas. Some of the pirates were those men who raided vessels with John West, Daniel Stillwell, Benjamin Hornigold, and John Cockram before 1716. These leaders started with a mix of local Bahamians and other strangers in groups of twenty-five men and smaller in periaugers and canoes. While they began using small sloops and shallops by 1714, many of these gangs of pirates remained small until 1715. In that year, Benjamin acquired a larger sloop, the Mary, which held a crew of one hundred and forty men, six guns, and eight patteraroes, a breech-loading swivel gun. While these predecessors remained pirates during the heydays of 1716-1717, the new arrivals soon outnumbered them.22

A significant amount of pirates came from the vessels that fished the Spanish wrecks. As time progressed, it became more difficult to work on the wrecks because of competition with other wreckers, Spanish guard vessels, and the exhausting of known wreck sites. Many of these wreckers, like other maritime opportunists before them, decided to pursue wealth through piracy, spurred on by the success of the Bahama pirates before 1716. As the Attorney General of South Carolina, Richard Allein, said to the jury at the trail of Stede Bonnet, “the great Expectations which so many had from the Bahama Wrecks, where not one in ten proved succesful, gave birth and increase to all the Pirates in those Parts, English, French, and Spaniards.”23 One particular group of about fifty men left the wrecks in early 1716 and settled in Nassau. These wreckers caused havoc among New Providence’s non-pirate citizenry. Their leader, Thomas Barrow, “a mate of a Jamaica brigantine which run away some time ago with a Spanish marquiss’s money and effects,” declared himself the Governor of New Providence.24 A number of the pirates in early 1716 claimed they would only attack Spanish and French ships.25 While some might have been honest and held loyalties to the British government, other pirates had different motives for these declarations. If the authorities deemed the British pirates outlaws, it would make returning home to their friends or families difficult and would complicate commerce with the merchants that sold the pirates supplies. Other pirates had little regard to the nationality of their prizes. Most talk of forgoing British and Dutch prizes disappeared by summer when it became clear that British authorities would turn against them. The arrival of King George I’s proclamation in Jamaica in late August of 1716, demanding the wreckers surrender themselves to the authorities by December 1, convinced many of the wreckers to continue pirate raids from their base in New Providence.26

In addition to the ex-wreckers, New Providence also welcomed many former logwood cutters. In 1715, the conflict between Spanish authorities and British logwood cutters boiled over into violence. By this year, nearly 2,000 men, many of them former mariners, cut logwood in a clandestine trade for British markets. This work employed a hundred vessels, often from New England, in carrying this logwood. These logwood cutters allowed Britain to compete with the French in the clothing dyes market. When Spain acted as an intermediary for this logwood, they sold it to the British at prices between £90 and £110 per ton. The British logwood cutters produced 12,000 tons of logwood a year and sold it for £9 per ton. The Spanish despised these “Bay-Men,” a term derived from their cutting wood in the Bay of Honduras and Bay of Campeche, and treated the logwood cutters, “as pyrates and thieves.”27 The Spanish sent ships to stop the Bay-Men’s operations. In September and October of 1715, two hundred to two hundred and fifty Bay-Men operating from two sloops and several periaugers began pirating from both the Honduras and Campeche bays.28 On November 30, a fleet of three Spanish sloops of war and a fire ship under the command of Don Alonso Philippe de Andrade arrived in the Bay of Campeche and forced the British ships in the bay to surrender and imprisoned their crews.29 Attorney General Richard Allein made the exaggerated claim that, “nine parts in ten of them [the logwood cutters] turned Pirates.”30 With opportunities to take treasure on the coast of Florida and Spaniards moving against their regular employment, New Providence soon received groups of these, “loose disorderly people from the Bay of Campeache, Jamaica, And other parts,” into their harbor, who began to collectively call themselves the, “Flying Gang.”31

Shelter, Trade, Food, and Rum: Living in Nassau

Excerpt from a map of the Bahamas featured in “The English Pilot. The Fourth Book” from 1716.

While five hundred to one thousands mariners, wreckers, bay-men, and other men turned pirate lived in or raided from Nassau, a small group of Bahama citizens remained on New Providence. In July of 1703, the Spanish and French left the settlement of Nassau in ruins. They burned most of the buildings on the island. Before these raids, Nassau featured, “about 250 white men, women and children, and as many blacks, molattoes and mustees, who live scattered in and about Nassau,” and, “about 300 houses little and great.”32 The 1703 raid and the attacks that followed caused many people to leave the Bahamas for the Carolinas, Virginia, New England, or anywhere they could procure passage. According to Governor Woodes Rogers, the inhabitants of the Bahamas told him the Spanish and French launched thirty-four raids of various sizes into the Bahamas in the fifteen years following the 1703 raid.33 The few remaining citizens of the Bahamas lived throughout the islands for the next decade, with no government, alone against the raids of their foreign enemies.

Until the pirates gained significant control of New Providence around 1715, an extremely small number of people with little means of defense inhabited the island. From 1707-1715, about six hundred people lived on the islands of Eleuthera, Harbour Island, and New Providence. Half of the population consisted of freemen. On New Providence, one report suggested thirty families remained, while another only mentioned 20 men among the people left on the island. In 1701, Governor Elias Haskett of the Bahamas described these European-descended residents of the Bahamas as having, “uneasy and a factious temper,… [they] neither believe that they out to be subject to the power of God or the commands of the King, not scrupling to do all manner of villany to mankind, and will justifie and defend others which have done the like.” This mindset led at least some of the local inhabitants to permit the pirate activities starting in 1713, or to take part in it themselves. The remaining few people on New Providence owned few arms and little ammunition when compared to the residents of Eleuthera or Harbour Island. In 1710, the New Providence residents possessed nine operational cannon taken from the fort, but no ammunition for them. The fort itself remained in ruins. With no tangible defenses left, New Providence’s citizens fled into the woods every time raiders arrived. Since they had no government to rely on or answer to, the small number of practically defenseless people left in Nassau and the greater Bahamas lived by the policy of, “the strongest man carrys the day,” with, “every man doing onely what’s right in his own eyes.”34

When New Providence became occupied by hundreds of pirates and the transients that followed them, the policy of “strongest man carrys the day” continued. While Hornigold claimed to protect all the pirates in New Providence, no clear chief ever arose in Nassau from 1716-1717, though one Philadelphia merchant believed Henry Jennings to be their leader, and the former wrecker Thomas Barrow whimsically declared himself governor of New Providence in 1716.35 The local citizens could do little to oppose the pirates for fear of retribution. The pirates robbed anyone they wish, and took anything they desired. If the pirates wished to burn someone’s residence, or if they desired to take a man’s wife, or wanted supplies, they did so unless met with enough opposition. Many citizens left New Providence to escape the pirates. If these local residents did not immediately obey the pirates, they faced threats and violence. In 1716, Thomas Barrow demanded twenty shillings from a Captain Stockdale and threatened to whip him if he did not pay. Stockdale submitted to the demands of Barrow and his friend Peter Parr, who gave, “a receipt on the publick account,” to Stockdale in return, probably in jest to Barrow’s claim of governorship.36

The pirates also threatened the last authority figure in the Bahamas, Thomas Walker, off New Providence. Walker possessed one of the few house estates left on the island, three miles outside of Nassau. When Benjamin Hornigold began mounting guns in what remained of the fort, Walker voiced his objections. Considering the two had already clashed over an incident involving local pirate and trader Daniel Stillwell, Hornigold threatened to shoot Walker. By July of 1716, Walker moved his family to a safer location on Abaco Island. The next month, Walker and his son went to Charleston and described the fear the non-pirate citizens of New Providence lived under while the pirates ruled the island.37

While these local inhabitants feared for their lives, the pirates shifted for themselves in the remains of Nassau. After repeated raids and fires, few of the post-and-beam-built houses remained standing. One of the few houses spared in Nassau in 1703 was the house of Bahama Governor Ellis Lightwood. When Woodes Rogers brought order and authority back to the Bahamas in 1718, he occupied one of the few remaining buildings in Nassau for his own residence. In 1707, a visiting captain reported only three houses stood outside of Nassau. The pirates allowed bushes to overgrow the town’s pathways, there being no substantial roads established in Nassau before Woodes Rogers’ governorship. The harbor’s main defense, a fort built during Nicholas Trott’s administration in the 1690s, laid in a ruined, yet repairable, condition.38 At least one pirate, Benjamin Hornigold, tried to build up the defenses of Nassau in 1716-1717. He worked to mount some artillery in the fort in 1716, though no reports recorded their number nor what remained of them by July of 1718 after Rogers’ arrival. On December 6, 1716, Hornigold captured a forty-gun Spanish vessel. Over three months later, a thirty-two-gun Spanish ship sat in the harbor as a guard vessel, more than likely Hornigold’s December capture with a few guns removed. Like the fort’s guns, no reports show what happened to the guard ship by the time of Roger’s arrival.39

Until more pirates began to populate the town just before 1716, residents lived in what shelters they could make within the remains of the buildings that stood before Spaniards and Frenchmen burned them to the ground during the previous war. Tents, lean-to shelters, hovels, and huts are typical types of shelters for frontier-like settlements such as Nassau in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Early residents spent little time building these structures since they only required basic shelters and knew the Spanish or French might soon return and burn them down. The most sizable and sturdy shelters among the citizenry were simply-designed huts that required few, if any, tools beyond felling axes. These huts used a simple construction and resembled those built by earlier settlers in the Bahamas of the previous century. Builders using this construction style split logs of cedar, pine, or thatch palmettos in half and then sunk them into postholes dug into the ground. The split logs formed the walls of a rectangular or square one-room hut.40 Bahama historians Michael Craton and Gail Saunders describe in detail the rest of the building process. After setting the split logs into the ground, builders:

…bound together [the log walls] with a single “plate rail” under eaves of slimmer split tree stems. Walls were made with wattles of woven mangrove stakes, daubed with a crude “cob” of limestone clay. The roof was covered with overlapped sheaves of stripped palmetto leaves, overhung to let most of the rainwater run off free. Most of the houses had a single doorway, and a window or two close under the eaves, with a door and shutters of simple battens to provide at least a modicum of privacy and security. None of the earliest houses had chimneys, cooking being done, then and later, in a separate shelter or cabin on the leeward side of the house, for safety’s sake.41

When pirates took over Nassau, they occupied the structures built by previous residents, made their own huts, or constructed other makeshift shelters. In his book about Woodes Rogers and the pirates of Nassau, David Cordingly postulated that, “The arrival of the pirates and logwood cutters must have led to the construction of some buildings on the waterfront for shipwrights and carpenters and for shops and taverns, but it seems likely that it was little more than a shanty town.”42 With no central governing body, the pirates possessed no rules for disposing of waste. As a result, human waste and garbage contributed to a gross stench throughout the town.43 It is from these makeshift homes that the pirates launched raids against the trade routes and coasts of the Americas.

While on New Providence, pirates caroused and spent time with women. After the pirates acquired plunder, they returned to the harbor of Nassau, “to sell and dispose of their piraticall goods, and perfusely spend [what] they take from ye English French and mostly Spaniards.” Locals and transients alike, hoping to profit from the pirates desires, served the pirates with, “entertaining and releiveing,” which included gambling, drinking, and prostitution.44 While their lifestyle in this era often resulted in erratic and unstable relationships with women, some pirates had wives in the Bahamas. In particular, several of the pre-1716 pirates were married, including John Cockram whose wife was the daughter of the wealthier Bahama resident Richard Thompson. These women managed households, tended crops, and cared for children while the pirates cruised for prizes. Women living in Nassau found themselves significantly outnumbered by men. Those who wished to make money off the pirates through prostitution could charge high prices for their services because of this disproportion. Women could also make money from services common in other ports, including the mending of clothes, laundry services, small-scale trading, and cooking. These women might have been Bahamians looking for wealthy husbands or desperate survivors looking for a living. Some may have been prostitutes from other ports who decided to pay for passage to Nassau so they could take advantage of the large number of men who had recently plundered fortunes in their pockets. An account of Anne Bonny included in Charles Johnson’s General History of Pyracy claims that she was the wife of a former pirate, named James Bonny, who had taken the royal pardon in 1718. At some point between 1718 and 1720, James caught Anne sleeping with another man. Later on, Anne began living with another pirate, John Rackham, who Anne depleted of money. It is still unclear what Anne Bonny’s origins were before this account and her brief two-month pirate career. It is possible that Anne was a prostitute while in Nassau, a profession some, but not all, women turned to while living among the pirates.45

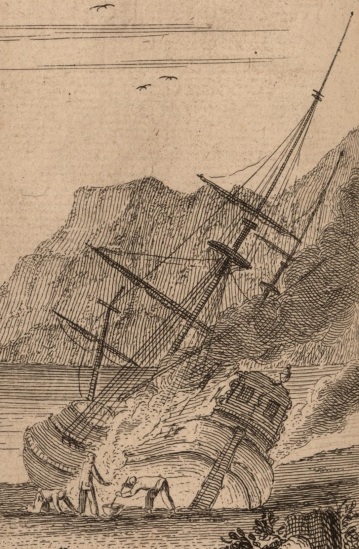

Excerpt from image of Capt. George Lowther and his Company at Port Mayo in the Gulf of Matique, 1734, showing pirates careening a ship. In this stage, the pirates are heating up tar so it can be smoothly applied to the hull of the ship.

Besides pay and pleasure, Nassau offered a place for refitting and resupply. Remnants of past repair work and the hulls of abandoned or burned prizes littered New Providence and its harbor. The pirates also used these shores to careen the hulls of their vessels. The removal of marine growth allowed ships to achieve their best speed possible while at sea. Pirate crews sold plundered cargo and purchased needed supplies, including food, weaponry, and ammunition. A few merchant vessels from other colonies traded in Nassau at their own risk. Some of these merchantmen became the victims of pirate attacks, sometimes in the harbor of Nassau itself. Be it a local non-pirate citizen of the Bahamas, colonial drifters, or a merchant wishing to buy pirate plunder for only a fraction of its value, everyone lived by the rule of, “the strongest man carrys the day.” The most secure vessels to trade with Nassau were local Bahama sloops from Harbour Island, where a small band of well-fortified Bahamians and fifty pirates lived and conducted business. Men such as John Cockram and Richard Thompson operated as intermediaries to merchants from several ports, including Boston, or sailed their own vessels of between fifteen and forty tons burthen to ports such as St. Thomas and Curaçao.46

To feed themselves on land and sea, pirates regularly pursued vessels at sea for provisions. The commodities most frequently taken were food, drink, and other personal necessities, as Dr. E. T. Fox demonstrated in a survey of goods stolen in eighty-eight documented cases.47 Considering that many pirates sailed together in large crews, which could vary from forty to over two hundred men, the frequent need to obtain more provisions is not surprising. It would have been difficult to gather enough locally produced foodstuffs to sustain all the pirates of Nassau. One typical example of pirates capturing a ship for provisions is Hornigold’s plundering of the Lamb on the night of December 13, 1716. The pirates took provisions that included, “Three Barrills of Porke, one of Beef, two of pease, three of Mackrill five Barrills of onions Several Dozen Caggs of oysters,” and only left the crew of the Lamb, “about Forty Biskets and a very Small quantity of meat just to bring them in [to Jamaica].”48 Based on food issued in the navy, the common diet of mariners consisted of bread, beef, pork, peas, fish, butter, and cheese.49 Since beer did not keep well in warm environments, most sailors and pirates drank rum, wines, or brandies. Mariners in the Caribbean held a strong and deserved reputation for consuming rum and for drinking it in large quantities, often watered down and mixed into rum punches. Sailors drank any alcohol available in the regions they lived or sailed. For the Caribbean, rum stood as the cheapest and most available drink for mariners and the general lower class. Pirates and sailors possibly consumed rum and other alcohols in such large and excessive quantities as a response to the anxieties caused while sailing at sea and poor living conditions.50

If pirates did not want their typical provisions while ashore, could not obtain them, or had property in the Bahamas, they probably consumed some of the local foodstuffs. Fish in the Bahamas were usually wholesome and plentiful, though some particular types of local fish made people severely ill after consumption. The islands had a few indigenous creatures, including lizards, iguanas, land crabs, coneys (a type of rabbit), sea turtles, and nine or ten types of non-migratory sea birds. The rest of the animals on the island included cows, sheep, hogs, horses, goats, rats, and dogs. Bahamians had access to a variety of fruits, including oranges, pine nuts, grapes, pomegranates, bananas, and plantains. For vegetables, the Bahama’s hot environment made planting difficult, but not impossible. Local farmers and garden plots produced Indian corn, guinea corn, peas, pumpkins, onions, manioc (also known as cassava), yams, groundnuts, pigeon peas, black-eyed peas, and other starch plants. While the pirates of Nassau ate more of the foods plundered from ships or purchased from merchants, at least some of the pirates consumed food produced in the Bahamas.51

* * *

The pirates of 1716-1717, a collection of mariners from the Bahamas, sailors from wrecking sloops of the Florida coast, logwood cutters from Central America, and others from throughout the Atlantic world, took over the desolate and ungoverned remains of Nassau and made it a base for raiding merchant vessels. When comparing the historical record to the appealing version of pirate ports presented in popular media, the lack of depth and character presented in the latter becomes more apparent. This is not surprising for a stereotype, though it does demonstrates the dangers they pose to the public’s understanding of the past. Today, the Bahamas’s tourist industry, the largest source of income for the islands, continues to use images reminiscent of the old pirate base stereotype. The cliché of the tropical pirate town attracts audiences since they can project the appeal of libertinism, exoticism, and the idea of a tropical paradise onto the legendary pirates of the early eighteenth century. The last idea, the enticement of the tropics, did not appeal to the greater populace until the end of the nineteenth century, when fruit companies, cruise lines, railroads, and other profit-seeking organizations convinced Americans and Europeans it was not only safe to visit tropical regions, they could also enjoy and prosper from trips to the sunny southlands.52

For the pirates of 1716, the Bahamas was a place with no official law and strategically located for raiding maritime commerce. The pirates did what they could with the remote island scorched by numerous raids. No other ports would welcome the pirates like others had in the seventeenth century. The Bahamas offered the pirates the port they needed. While it sat on a pile of ashes in the middle of thousands of sun-baked islands, the pirates took the opportunity and created a reputation for Nassau that reverberated through the Atlantic World of the eighteenth century and established a legacy, which still persists in the public’s memory.

Postscript: This post was inspired by a question asked by Jacqui Sive of South Africa and by others on social media who have previously asked questions about life in the Bahamas during the years it was occupied by pirates. For a book that covers the history of the Bahamas, and includes the period when pirates occupied the islands, the most comprehensive and current scholarly text is Islanders in the Stream, A History of the Bahamian People, Volume 1, by Michael Craton and Gail Saunders. This publication covers the history of the Bahamas from roughly 500 A.D. to 1834.

† Today, Bahamians call this small island Paradise Island. The origin of the name Hogg Island, or Anne Island in some early documents, supposedly came from Bahama Governor Nicholas Trott, who grew up on Bermuda at a place called Hog Bay. Trott bought what became Hogg Island from the Lords Proprietors for £50 in 1698 after his brief tenure as governor. One other possibility is the name refers to actual hogs, to particular tree on the island, or to both. Mark Catesby’s natural history of the Bahamas mentioned Hogg Island was, “covered with Palmeto.” Catesby’s history also mentioned the hog palmetto, noting, “the Trunks alone of these Trees is an excellent Food for Hogs; and many little desart Islands, that abound with them, are of great use to the Bahamians for the Support of their Swine.” In 1723, the new government of the Bahamas made a law that forbade citizens from shooting livestock on Hog Island, including hogs. Considering there were hogs on the island and that it probably featured hog palmetto trees, there is a strong chance that Hogg Island gained its name from the hogs and hog palmettos trees. The greater eastern seaboard witnessed many small other islands with the name hog island since Europeans frequently placed hogs on small islets for better protection and management. The islands where they raised these hogs eventually gained the name of Hog Island. Sources: Paul Albury, Anne Lawler and Jim Lawlor, The Paradise Island Story, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Macmillan Caribbean, 2004), 11-12, 14-15, 23; Catesby, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, xxxviii, xli; Anderson, Virginia DeJohn. “King Philip’s Herds: Indians, Colonists, and the Problem of Livestock in Early New England.” The William and Mary Quarterly 51, no. 4 (October 1994): 601, 618.

‡ The channels surrounding the Bahamas have held various names over time. The Florida Straits went by several names during the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, including the Gulf of Florida, the Gulf of Bahama, and the New Bahama Channel.

Endnotes

- John Graves, Memorial: Or, a Short Account of the Bahama-Islands (London: [no publisher listed], 1707), 5-7.

- John Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, Containing The History of the Discovery, Settlement, Progress and Present State of All the British Colonies, on the Continent and Islands of America (London: Printed for John Nicholson, Benjamin Tooke, Richard Parker, and Ralph Smith, 1708), 2: 350.

- The English Pilot. The Fourth Book. Describing the West-India Navigation, from Hudson’s Bay to the River Amazones (London: Rich. and Will. Mount, Tho. Page, 1716), 49.

- “Capt. Chadwell, of the Flying-Horse sloop, to Robt. Holden. Oct. 3, 1707,” The Calendar of State Papers, Colonial Series, (from now on abbreviated CSPCS) 1706 -1708 June, ed. Cecil Headlam, item 1128; Mark. Catesby, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands (London: Charles Marsh, Thomas Wilcox, and Benjamin Stichall, 1754), 1: xxxviii, xlii; “E. Randolph to the Council of Trade and Plantations, March 5, 1701,” CSPCS, 1701, item 208; Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 2:556. There are no fresh-water rivers or springs in the Bahamas, only tidal creeks, meaning locals had to rely on reservoirs or ponds for fresh drinking water.

- Graves, Memorial, 5; Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 2:349.

- Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 356; Charles Johnson, A General History of the Pyrates (1724), ed. Manuel Schonhorn (Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press, 1972), 37.

- Catesby, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, xxxviii; Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 356; The English Pilot, 46; Letter of Captain Vincent Pearse, 3 June 1718, ADM 1/2282, TNA.

- Graves, Memorial, 3.

- Ibid.; Oldmixon, The British Empire in America, 358; “E. Randolph to the Council of Trade and Plantations, March 5, 1701,” CSPCS, 1701, item 208.

- The English Pilot, 46-47.

- “Boston,” Boston News-Letter, March 29-April 5, 1714; “Sir Thomas Lynch to the Governor of New Providence, [August 29, 1682, Jamaica],” CSPCS, 1681-1685, item 668i.

- “Accot. of Piratts and the State and Condition the Bohamias are now in Rendered by Thomas Walker, New Providence, March 12, 1714[-15],” CO 5/1264, No. 17i, TNA.

- “Deposition of John Vickers, late of the Island of Providence, [1716],” CSPCS, Jan. 1716 – July, 1717, item 240i.

- “Archival Information on the 1715 Fleet, Compiled by Jack Haskins,” trans. Dr. Nancy Farriss, eds. Box Marx and J. M. Rodriquez Jr. (Islamorada, FL: Unpublished manuscript of Monroe County Public Library), 3-4; The conversion of Spanish money to British money comes from using the official conversion rate of the era, as published in the E. Chambers, Cyclopaedia: Or, an Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (London: Printed for James and John Knapton, et al, 1728), 1: s.v. “Coin”. One peso, or one piece of eight, is worth four shillings and six pence, or £0.04.06 in the early eighteenth century. Sums of British currency listed in pounds, shillings, and pence will utilize this format: £[Pounds Here].[Shillings Here].[Pence Here]. The conversion rate is official, but actual value may vary slightly between circumstances. For instance, a man from London, named John Southhall, travelling in Jamaica in 1726 stated that one bit, or one real (one eighth of a Spanish piece of eight) to be worth seven pence and half penny. Unless he was ill-informed at the time of proper exchange rates, Southall’s statement on the value of one bit in Jamaica would mean a piece of eight was worth five shillings instead of £0.04.06. It could have been a mistake, or it could be an indicator of hard currency’s value and scarcity in the colonies. For Southall reference, see: John Southall, A Treatise of Buggs (London: Printed for J. Roberts, 1730), 8.

- “Archival Information on the 1715 Fleet,” 4.

- “Rhode Island, Decemb. 16,” Boston News-Letter, December 12-19, 1715 “New York, December 19,” Boston News-Letter, December 26 to January 2, 1715[-16]; “New York, May 21,” Boston News-Letter, May 21 – May 28, 1716; “Captain Balchen, H.M.S. Diamond, to Mr. Burchet, May 13, 1716, The Nore,” CSPCS, Jan. 1716 – July 1717, item 158iv; “List of [10] Vessels Commissioned by Governor Lord A. Hamilton Delivered by Mr. Page, Deputy Secretary of Jamaica, to the Secretary of State, [1717],” CO 152/11, no.16ii, TNA; Lt. Governor Bennet to Mr. Popple, Aug 8, 1716. CSPCS, Jan. 1716 – July 1717, item 300; “Declarations of Pedro de la Vega,” Consulado de Cadiz, legajo 853, Archivo General de las Indias, Sevilla, España (from now on abbreviated AGI); “Declaration of Agustin Castellanos,” Consulado de Cadiz, legajo 853, AGI; “Declaration of Bartolome Carpenter, June 24, 1716 [Gregorian Calendar, is June 13 on Julian Calendar]” Consulado de Cadiz, legajo 853, AGI.

- “Captain Balchen, H.M.S. Diamond, to Mr. Burchet, May 13, 1716”; “List of [10] Vessels Commissioned by Governor Lord A. Hamilton.”

- “Deposition of Joseph Lorrain, August 21, 1716, Jamaica,” Jamaica Council Minutes, ff.110-111, Jamaica National Archives, Spanish Town, Jamaica; “Extract of a letter from Don Juan Francisco del Valle to the Marquis de Monteleon, March 18, 1716,” CSPCS, Jan. 1716 – July 1717, item 158i; “Declaration of Antonio Peralta,” Consulado de Cadiz, legajo 853, AGI; “Declarations of Pedro de la Vega.”

- “Declaration of Bartolome Carpenter, June 24, 1716.”

- “Capt. Mathew Musson to the Council of Trade and Plantations, July 5, 1717, London,” CSPCS, Jan. 1716 – July 1717, item 635; “James Logan to Robert Hunter, Oct. 24, 1717,” James Logan Papers, misc. vol. 2, p. 167, Historical Society of Pennsylvania; “Lt. Governor Bennett to the Council of Trade and Plantations, July 30, 1717, Bermuda,” CSPCS, Jan. 1716 – July 1717, item 677; “Lt. Governor Bennet to the Council of Trade and Plantations, May 31, 1718, Bermuda,” CSPCS, Aug. 1717 – Dec. 1718, item 551.

- Letter of Captain Vincent Pearse, 3 June 1718.

- “Boston,” Boston News-Letter, March 29-April 5, 1714; “Accot. of Piratts and the State and Condition the Bohamias are now in Rendered by Thomas Walker, New Providence, March 12, 1714[-15]”; “Deposition of John Vickers, late of the Island of Providence, [1716]”; “Lt. Governor Pulleine to the Council of Trade and Plantations, April 22, 1714, Bermuda,” CSPCS, July 1712 – July 1714, item 651

- “The Tryal of Major Sted Bonnet, and Other Pirates [1719],” in British Piracy in the Golden Age: History and Interpretation, 1660-1730, vol. 2, ed. Joel Baer (London: Pickering & Chatto, 2007), 338.

- “Deposition of John Vickers, late of the Island of Providence, [1716].”

- Ibid., “New York, May 21” Boston News-Letter, May 21 to May 28, 1716; “Lieutenant Governor Spotswood to the Lords of the Admiralty, July 3, 1716,” in Alexander Spotswood, The Official Letters of Alexander Spotswood, Lieutenant-Governor of the Colony of Virginia, 1710-1722, ed. R. A. Brock (Richmond, VA: The Society, 1885), 2:168. The Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 officially ended the War of Spanish Succession in which Britain fought against France and Spain.

- “Spotswood to the Lords of the Admiralty, July 3, 1716”; “A Proclamation Concerning Pyrates, August 30, 1716, Jamaica,” Jamaica Council Minutes, ff.153-155, Jamaica National Archives, Spanish Town, Jamaica.

- “Thomas Bannister to the Council of Trade and Plantations, July 7, 1715.” CSPCS, August, 1714 – December, 1715, Item 508; “The case of the proposall for preventing the French South Sea Trade from being carried on from France provided the English clandestine trade with the Spaniards in the West Indies be also prevented, Oct. 28, 1714” CSPCS, August, 1714 – December, 1715, item 129ii; The state of the island of Jamaica. Chiefly in relation to its commerce, and the conduct of the Spaniards in the West Indies (London: H. Whitridge, 1726), 15-16.

- “Rhode-Island, Septemb. 16,” Boston News-Letter, September 12-19, 1715; “New York, October 3” Boston News-Letter, October 3-10, 1715.

- “Deposition of Simon Slocum, William Knock, Paul Gerrish, John Tuffton and Thomas Porter, Feb. 28th, 1716,” CSPCS, Jan. 1716 – July 1717, item 484ii.

- “The Tryal of Major Sted Bonnet, and Other Pirates [1719],” 338.

- “Lieutenant Governor Spotswood to the Lords Commiss’rs of Trade, July 3, 1716, Virginia”; “Deposition of John Vickers, late of the Island of Providence, [1716].” The term “Brethren of the Coast” does not appear in period documents discussing the pirates that sailed in the early eighteenth century, the term appears in Alexandre Exquemelin’s Buccaneers of America, which described the pirates of the 1660s and 1670s.

- Oldmixon, John. The British Empire in America, 359-360; “Governor Haskett to the Council of Trade and Plantations, July 19, 1701, New Providence,” CSPCS, 1701, item 655; “E. Randolph to the Council of Trade and Plantations, March 5, 1701,” CSPCS, 1701, item 208.

- Oldmixon, John. The British Empire in America, 360; “Governor Rogers to the Council of Trade and Plantations, May 29, 1719, Nassau on Providence,” CSPCS, Jan. 1719 – Feb. 1720, item 551.

- “Capt. Chadwell, of the Flying-Horse sloop, to Robt. Holden. Oct. 3, 1707”; “Lt. Governor Pulleine to the Council of Trade and Plantations, April 22, 1714, Bermuda”; “Governor Haskett to the Council of Trade and Plantations, July 19, 1701”; “Copy of letter from Capt. Smith, H.M.S. Enterprize, Kiquotan, Virginia, August 12, 1710,” CSPCS, 1710 – Jun. 1711, item 421i.

- “Deposition of John Vickers, late of the Island of Providence, [1716]”; “James Logan to Robert Hunter, Oct. 24, 1717.”

- “Deposition of John Vickers, late of the Island of Providence, [1716].”

- Thomas Walker to the Council of Trade and Plantations, South Carolina, August 1716, CO 5/1265 no.52, TNA; “Deposition of John Vickers, late of the Island of Providence, [1716]”; Deposition of Thomas Walker Jr., South Carolina, August 6, 1716, CO 5/1265 no. 52i, TNA; “Copy of letter from Capt. Smith, H.M.S. Enterprize, August 12, 1710.”

- David Cordingly, Spanish Gold, Captain Woodes Rogers and the Pirates of the Caribbean. London: Bloomsbury, 2011), 154; Oldmixon, John. The British Empire in America, 356, 359; “Capt. Chadwell, of the Flying-Horse sloop, to Robt. Holden. Oct. 3, 1707”; Thomas Walker to the Council of Trade and Plantations, South Carolina, August 1716; Deposition of Thomas Walker Jr., South Carolina, August 6, 1716; ; Michael Craton and Gail Saunders, Islanders in the Stream: A History of the Bahamian People, vol. 1. (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1992), 84.

- Thomas Walker to the Council of Trade and Plantations, South Carolina, August 1716; “Capt. Mathew Musson to the Council of Trade and Plantations, July 5, 1717,”; Deposition of Henry Timberlake, 17 December 1716, 1B/5/3/8, 426, Jamaica National Archives, Spanish Town, Jamaica.

- “Capt. Chadwell, of the Flying-Horse sloop, to Robt. Holden. Oct. 3, 1707”; Catesby, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, xxxviii, xli; Cary Carson, Norman F. Barka, William M. Kelso, Garry Wheeler Stone, and Dell Upton, “Impermanent Architecture in the Southern American Colonies.” Winterthur Portfolio 16, no. 2/3 (1981): 139-141; Craton and Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 82-83; Arne Bialuschewski, “Pirates, Markets and Imperial Authority: Economic Aspects of Maritime Depredations in the Atlantic World, 1716–1726.” Global Crime 9, no. 1–2 (2008): 55-56.

- Craton and Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 83.

- Cordingly, Spanish Gold, 154.

- Ibid., 154-155; Bialuschewski, “Pirates, Markets and Imperial Authority,” 55-56.

- Thomas Walker to the Council of Trade and Plantations, South Carolina, August 1716.

- “Lt. Governor Pulleine to the Council of Trade and Plantations, April 22, 1714”; “Accot. of Piratts and the State and Condition the Bohamias are now in Rendered by Thomas Walker, New Providence, March 12, 1714[-15]”; Craton and Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 90; John Appleby, Women and English Piracy: 1540-1720, Partners and Victims of Crime (Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press, 2013), 102-103, 120-121; Johnson, A General History of the Pyrates, 623. Note that this account of Anne Bonny came from an appendix to the first volume of this history. While no other document has yet corroborated this story, the appendix features information potentially provided from Woodes Rogers, who had to deal with Anne Bonny while he was Governor of the Bahamas, raising the probability of this story being true. The account does not directly state if Anne Bonny was a prostitute, only vague references to engaging in “libertinism” and taking money from John Rackham.

- Cordingly, Spanish Gold, 151; “Accot. of Piratts and the State and Condition the Bohamias are now in Rendered by Thomas Walker, New Providence, March 12, 1714[-15]”; “Deposition of John Vickers, late of the Island of Providence, [1716]”; Thomas Walker to the Council of Trade and Plantations, South Carolina, August 1716; “Capt. Mathew Musson to the Council of Trade and Plantations, July 5, 1717”; “Capt. Chadwell, of the Flying-Horse sloop, to Robt. Holden. Oct. 3, 1707”; “Lt. Governor Pulleine to the Council of Trade and Plantations, April 22, 1714”; “Council of Trade and Plantations to Mr. Secretary Addison, May 31, 1717, Whitehall,” CSPCS, Jan. 1716 – July 1717, item 596.

- E. T. Fox, “‘Piractical Schemes and Contract’: Pirate Articles and Their Society, 1660-1730,” (Ph.D. diss., University of Exeter, 2013), 131.

- Deposition of Henry Timberlake, 17 December 1716.

- James Love, The Sea-Man’s Vade Mecum (London: James Woodward, 1707), 149.

- Frederick Smith, Caribbean Rum: A Social and Economic History (Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2005), 136-140; Janet MacDonald, Feeding Nelson’s Navy: The True Story of Food at Sea in the Georgian Era (London: Chatham Publising, 2004) 41-43. It is a misconception that alcohol acting as a long-term replacement for drinking water. People of this era drank plenty of water when it was available. As for the power of rum, Jane MacDonald estimates eighteenth-century rum to have been five or six times as powerful as modern consumer rum. In addition, the word “grog” was not invented until the 1740s, precluding its use during the Golden Age of Piracy.

- Craton and Saunders, Islanders in the Stream, 82; Catesby, The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, xlii, 358; “Capt. Chadwell, of the Flying-Horse sloop, to Robt. Holden. Oct. 3, 1707”; “Governor Haskett to the Council of Trade and Plantations, July 19, 1701.”

- Catherine Cocks, Tropical Whites: The Rise of the Tourist South in the Americas (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013).

I am really enjoying the theme/design of your site.

Do you ever run into any web browser compatibility problems?

A couple of my blog readers have complained about my website not operating correctly in Explorer but looks great in Firefox.

Do you have any solutions to help fix this issue?

I am not that big of a blogger, so I am not good at fixing issues with blogs. I use templates provided by WordPress. I have yet to have a problem brought to my attention concerning internet browser issues. Thank you for the compliment though on the layout.

I am genuinely happy to read this web site posts which contains lots of valuable information,

thanks for providing such data.

Hmm it seems like your blog ate my first comment (it was super

long) so I guess I’ll just sum it up what I submitted and say, I’m thoroughly enjoying your blog.

I too am an aspiring blog blogger but I’m still new to the whole thing.

Do you have any tips for newbie blog writers? I’d certainly appreciate it.

Write what you know, and while quantity will get your visitor numbers up, quality will keep them coming back.

Well done, David!

Well done, David.

Excellent job, David!