Excerpts from “The Sailor’s Parting,” by C. Mosley, 1743. The image includes depictions of a hammock, sea chest (with initials), and simple bag.

The sea chest is a common piece of material culture seen among stereotypes of pirates and sailors in the Age of Sail. Many people imagine a variety of items locked away within these chests, from fascinating tools of the seafaring trades to treasure plundered during many adventures at sea. In the realm of stories about pirates, Billy Bones owns the most famous sea chest of all fictional pirates. In Robert Lewis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, originally published as a serial in Young Folks magazine from October of 1881 to January of 1882, Bones was the first mate of the pirate Captain John Flint. The exterior of Billy’s sea chest was, “somewhat smashed and broken as by long, rough usage,” with a “B” burned to its top. Stevenson described the contents of the sea chest in detail, including items concerning the story’s treasure, such as Bones’ account book, a bar of silver, a bag of coins, and a treasure map. Beyond these pieces concerning the treasure, the chest contained a suit of clothes, “a quadrant, a tin canikin, several sticks of tobacco, two brace of very handsome pistols,…an old Spanish watch and some other trinkets of little value and mostly of foreign make, a pair of compasses mounted with brass, and five or six curious West Indian shells… [and] Underneath there was an old boat-cloak, whitened with sea-salt on many a harbour bar.”1 Contents such as these are typical by the standards of the modern stereotype of sailors and pirates in the Golden Age of Piracy. When compared to the historical record, with exception to the treasure items, how accurate is Stevenson’s depiction? What did Anglo-American sailors or pirates of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries own? Broadly speaking, some sailors of the era did own the kind of items seen in Stevenson’s stereotypical sea chest. However, examining the historical record for traces of sailors’ possessions provides some insight into the lives of mariners in this era. Continue reading

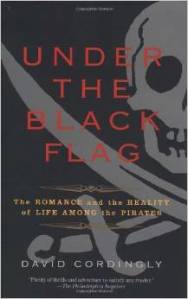

In the 1990s, David Cordingly’s work on historical pirates helped revive public interest in pirate history. His book, Under the Black Flag, presents much of the work presented in those efforts in an accessible style for mainstream readers. Cordingly presents a variety of topics on pirate history, including myths concerning pirates, Hollywood’s relationship to pirate history, general aspects of pirate life, and quick surveys of several pirates in history, including Henry Morgan and Captain Kidd. While the errors in his text and strange organization of his topics can be hindering at times, it is still a serviceable general introduction to pirate history. Specifically, this book will greatly assist anyone who never read about pirate history and has only encountered them in the way Hollywood presents piracy. The first chapter is particularly effective in dispelling many of the myths and Hollywood stereotypes that conflict with the historical record. For academic historians, Under the Black Flag is also a valuable piece since it is significant for those studying the historiography of pirate history.

In the 1990s, David Cordingly’s work on historical pirates helped revive public interest in pirate history. His book, Under the Black Flag, presents much of the work presented in those efforts in an accessible style for mainstream readers. Cordingly presents a variety of topics on pirate history, including myths concerning pirates, Hollywood’s relationship to pirate history, general aspects of pirate life, and quick surveys of several pirates in history, including Henry Morgan and Captain Kidd. While the errors in his text and strange organization of his topics can be hindering at times, it is still a serviceable general introduction to pirate history. Specifically, this book will greatly assist anyone who never read about pirate history and has only encountered them in the way Hollywood presents piracy. The first chapter is particularly effective in dispelling many of the myths and Hollywood stereotypes that conflict with the historical record. For academic historians, Under the Black Flag is also a valuable piece since it is significant for those studying the historiography of pirate history.